THEBES

Home > The axe collection >Thebes

Replica of crescentic axe from Thebes, EgyptWeight: 170 grams - Total width: 21.7 cm - Material: low tin-bronze (Cu95Sn5) Edge: several cycles of annealing, hardened through cold hammering - Original: (British Museum EA30068, presumably from Thebes, Egypt) |

||

|---|---|---|

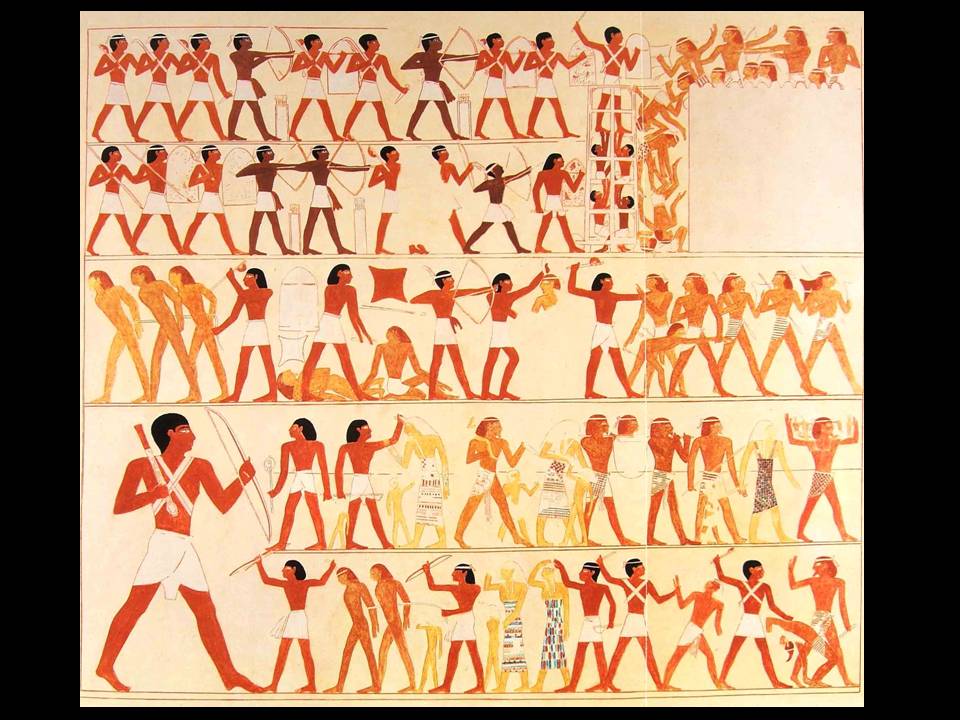

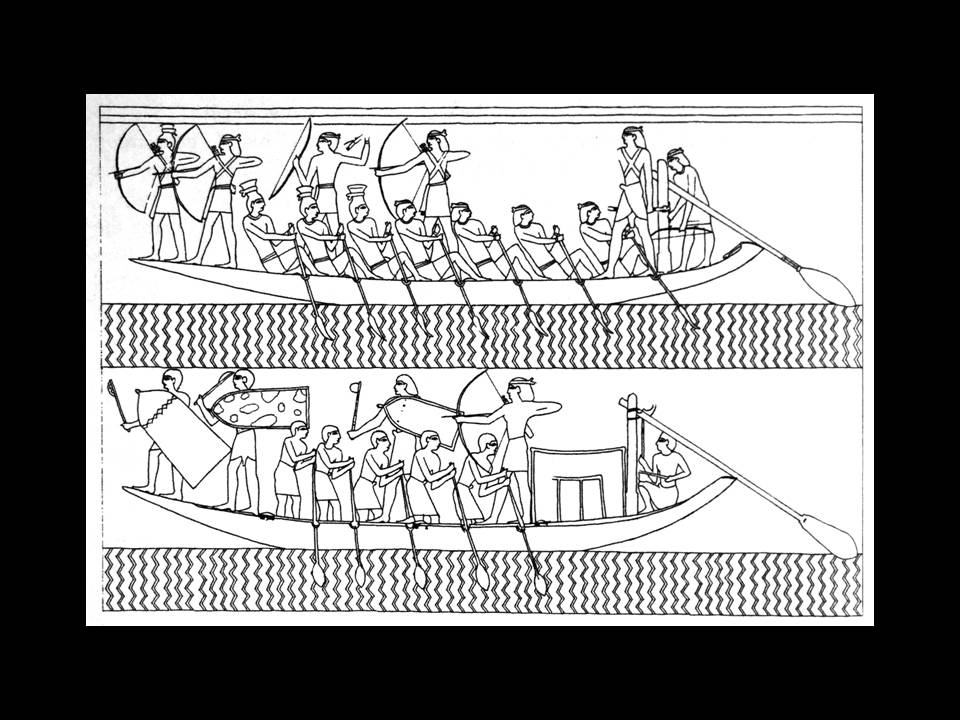

THE EGYPTIAN CRESCENTIC AXEOne of the best illustrations of the cresentic axe in action is found in the tomb of Intef at Thebes. According to the tomb paintings, Intef, overseer of troops (general) and right hand of king Mentuhotep II, led a siege against a fortress in Canaan as well as a battle at sea. These battles occurred during the reign of Mentuhotep II, around 2000 BC, at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom. In these depictions crescentic axes are hafted on straight shafts. The crescentic axe had spread to Egypt some time before 2000 BC, probably through contacts with Retennu (Canaan/Syria-Palestine). The Egyptian army stuck to their simple axes – the D-shaped axe, the flat axe and the crescentic axe – through the Middle Kingdom. All had rather simple facilities for hafting. The rawhide lashings must have been particularly vulnerable – if these were cut by an opponent’s axe, the blade would soon come loose and become useless. Although the New Kingdom brought innovations in haft shapes and axe types, Egyptian soldiers continued to used simple flat axes fastened with rawhide binding to the end of the Bronze Age. |

||

|

Thebes, copy of painting in the tomb of general Intef, showing siege of Canaanite fortress |

|

|

Thebes, copy of painting in the tomb of general Intef, showing battle at sea. |

|

Tin also entered the Near East in greater quantities in the centuries before 2000 BC. This tin most likely came from the east, from modern Afghanistan. The Egyptians probably traded their tin from their contacts in Canaan, and we could assume that levels of tin were lower in Egypt than in Canaan (where we have much more information on alloys used). A bronze with 5% tin has been used in the replicated axe – resulting in a reddish hew to the axe. The 5% tin is still enough to increase the potential hardness of the material obtainable through hammering of the edge. The edge of the Thebes replica axe has been annealed and hammered in several cycles, before final grinding. There seem to have been two methods for hafting: rivets or binding. In both cases the tangs of the axe are fitted to slots in the haft. The specimens with rivets seem all to have holes near the edge of the tangs, while specimens with binding have holes further in on the tangs. Thus I have concluded that the replicated axe from Thebes was most likely fastened with binding, not rivets. I have not been able to find evidence of linen/flax binding (only on museum reconstructions), but several specimens with rawhide binding (contemporary axes, although different types). Preserved hafts have a round cross-section and are most often straight.

|

||

|

The Thebes replica during heat treatment and edge hardening. |

|

|

Axe with D-shape with a complete haft - straight, sylindrical, with metal cap on top. Binding lost. Haft C-14 dated to 1870+/-120BC. British Museum (EA30083) |

|

|

Crescentic axe from Thebes with tubular casing of silver. British Museum (EA36776) |

|

|

Long crescentic axe with complete haft from Tuna el-Gebel, Egypt. The haft seems to be a branch, 107cm long. Older photo shows that the binding is recent, made at the museum. Metropolitan Museum. |

|

|

||